Violence against the uterus

Nestled deep within the body, hidden from view, the uterus may appear to be protected, inaccessible, and therefore safe from various forms of violence. However, it is a prime target when it comes to consciously or unconsciously putting pressure on those who carry it, coercing them, hurting them in order to keep them in a subordinate position. The uterus is fully integrated into the domination mechanisms that have made women a minority that they are not. As such, the organ, the embodiment of a sex and the maternal function assigned to it, is the object of specific and multifaceted forms of violence.

Verbal abuse

No uterus. No opinion: this slogan has been seen frequently in recent years at demonstrations and marches by or for women around the world, particularly in the United States under Donald Trump (fig. 1). It expresses the demand for the right of women to be the sole decision-makers in all matters relating to their bodies, particularly in the context of abortion rights and access. It is also a fight against the centuries-old injunctions that weigh on women and their uteruses and impose social norms (pregnancy, age at which it occurs, partner, etc.) that they sometimes come to consider legitimate.

This slogan was popularized by the American TV series Friends, although it did not originate there. In episode 14 of season 8, Rachel, who is pregnant, experiences severe pain in her uterus and has to be taken to the hospital, where tests reveal that she is suffering from Braxton Hicks contractions. Ross, the father of the unborn child, when he learns the nature of her pain, condescendingly announces that most women don't even experience this type of contraction. That is when she hits him with the famous line. Since then, it has been widely used by feminist movements. While Rachel’s intention was to highlight men’s inability to understand and empathize with the sensations of pregnancy because they cannot experience them themselves, the meaning of the phrase is much broader in an activist context. “No uterus, no opinion” now symbolizes the feminist ambition to fight against violence, particularly verbal violence, directed at this organ.

The uterus is also a target of violence due to the ignorance to which it has long been subjected, particularly with regard to the pathologies that affect it. Such ignorance about the organ leads to a disregard for women’s suffering.

Medical violence

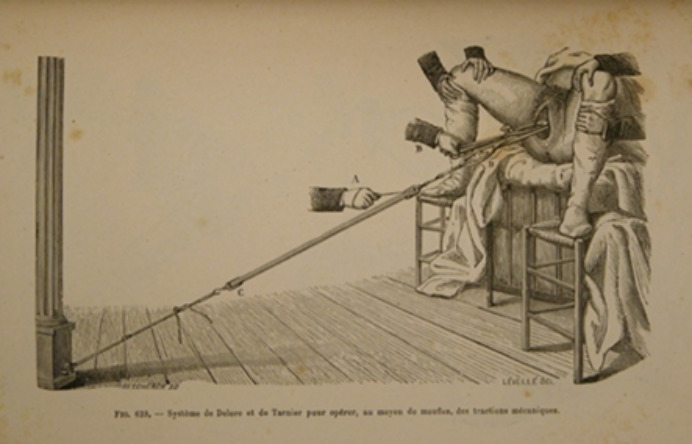

This denial of women’s pain has also led to violence against the organ under the pretext of treating it. The result—the cure of a disease— takes precedence over the will and well-being of the patient and leads ultimately to accepting violence as legitimate because it has a laudable goal. These considerations are also valid in the field of obstetrics, where being able to choose the conditions of childbirth is a recent and not universal privilege. Women’s medicine, and gynaecology in particular, has ancient origins, with the first treatises on the subject dating back to Antiquity. However, interest in and study of this field does not necessarily translate into kindness and consideration for the patient. Many 19th-century medical works show a series of instruments and practices designed to treat the female genital area or assist in delivery, but which, at the same time, constitute an arsenal of suffering for the organ. Figure 2, taken from a book on the history of childbirth, shows—among the many instruments invented during this period—a device designed by two French doctors (X. Delore and S. Tarnier) to speed up childbirth using a mechanical traction system. However, the machine did not replace human action, as several (male) hands are clearly visible on the female body.

Political and economic violence

From the late 19th century to the present day, women's wombs have also been the target of eugenicist or Malthusian state policies carried out without the consent of those most affected. Numerous forced sterilization campaigns have been carried out around the world, mainly targeting indigenous women, poor women, and/or women suffering from mental illness (in Nazi Germany, Réunion, Peru, Canada, India, etc.). The creation by Peruvian feminist visual artist María María Acha-Kutscher (fig. 4) for the exhibition INDIGNADAS/Latin America pays tribute to these women who were sterilized against their will in Peru. It is inspired by the demonstrations organized by the collective Somos 2074 y muchas más: during these performances, to remind people of the mutilations they suffered, the activists wear Andean skirts that they lift up, revealing a placard with a black-painted uterus from which red blood flows. The artist uses the colours used in these parades in her work. She is thus fighting for recognition of the harm suffered by thousands of women who, in the 1990s, were subjected to surgical procedures that rendered them unable to have children as part of President Alberto Fujimori's birth control policy. Health centres had to meet sterilization quotas in exchange for international development aid, which led to the mutilation of thousands of Native American women. Today, feminist movements in South America are working together to end specific forms of violence against women—sexual violence and femicide—and to fight against land grabbing, in a movement to defend “the body-territory and the territory-Earth” (Lorena Cabnal, a leading figure in community feminism in Guatemala).

Other regions are also affected by such violence. In India, birth control policy is mainly enforced through sterilization. Some Indian states do not hesitate to offer financial compensation to women who agree to undergo the operation, using misleading information, in particular by lying about the irreversible nature of the procedure, to persuade them. These operations have also been performed on men, also under duress, since the 1950s.

These practices, which primarily affect poor women, also have economic implications. In May 2019, a scandal erupted in India when NGOs revealed that thousands of women working on sugar cane plantations in the state of Maharashtra had been subjected to forced hysterectomies since the 1990s in order to increase their productivity. Photojournalist Chloé Sharrock travelled to India in October 2019 to meet these women. Her exhibition, entitled Sugar Girls, is being presented as part of the Visa Pour L’image 2020 festival. Among the 25 photos, mainly portraits, one (fig. 5) focuses on the scar on the stomach of a 29-year-old woman, Asha, who was married at 12, became a mother at 14, underwent a hysterectomy at 27, and whose physical condition has continued to deteriorate ever since.

The context of war has also long been conducive to violence against women through direct attacks on their bodies.

Rape is a weapon of war that terrorizes and fascinates, as evidenced by this 1909 lithograph by Gottfried Sieben (fig. 5). Among the twelve scenes that the Austrian illustrator and writer devotes to the atrocities of war in his pamphlet Balkangreuel (“Atrocities in the Balkans”), all depict violence against women, as in this figure where several of them, largely naked, try unsuccessfully to escape their attackers. These images of rape committed by the Ottoman army are part of an Orientalist and racist stereotype; they also allow the artist to exploit female bodies by sexualizing them. For him, it is not so much a question of denouncing these rapes as of producing a highly erotic piece of anti-Ottoman propaganda. The violence is therefore both in the reality of the practices depicted and in the fantasies they arouse.

The uterus is the direct target of these war rapes, as they are committed with the aim of permanently mutilating it or impregnating the victims in order to destroy the enemy. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Dr. Mukwege, a gynaecologist and 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner, performed reconstructive surgery on women who had been raped, whose vaginas had been shot at or had machetes, knives, or various objects inserted into them in order to render them unable to procreate. His work restores not only the flesh but also the victims’ dignity. Forced pregnancies following rape are also seen as a means of eradicating an adversary and have contributed to the conceptualization of rape as a weapon of genocide, recognized as a crime against humanity since 1993. Rape is used as a means of disrupting enemy populations. The process of destruction and appropriation goes even further when pregnancies are imposed, because it is not only the land that is invaded, but the cohesion of the group that is broken.

Bibliography

M. Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

N. Battesti, « Le viol, une arme de guerre multiséculaire ? », in J. Baechler, M. Trévisi (dir.), La guerre et les femmes, Paris, Hermann, 2018, p. 95-121.

J. Falquet, « “Corps-territoire et territoire-Terre” : le féminisme communautaire au Guatemala. Entretien avec Lorena Cabnal », Cahiers du Genre, 59, 2, 2015, p. 73-89.

F. Regard (éd.), Féminisme et prostitution dans l’Angleterre du XIXe siècle : la croisade de Josephine Butler, Lyon, ENS Éditions, 2014.

F. Vergès, Le ventre des femmes. Capitalisme, racialisation, féminisme, Paris, Albin Michel, 2017.

| An organ of globalization | Violence against the uterus | Feminist demands and the uterus |