An organ of globalization

Although it is a priori fixed, nestled in the hollow of the body, the uterus is nevertheless an organ that provokes circulation. Since ancient times and up to the present day, it has sparked the circulation of knowledge and techniques around the world. We are also witnessing a contemporary globalization around surrogacy and the defence of the reproductive and contraceptive rights of people with uteruses. Finally, in even more recent times, the organ as a symbol has also become globalised.

The uterus, an organ that stimulates circulation around the world

The globalisation of the uterus has been evident since ancient times, with the circulation of knowledge and techniques, particularly gynaecological ones, in the Mediterranean. For example, the Hippocratic Collection, which originated in Greece in the 5th century BC, was taken up and adapted by Galen in Rome in the 2nd century AD. In the Middle Ages, the Salerno School of Medicine incorporated knowledge from Antiquity and several cultures, including Greek, Byzantine, and Arabic, as it was open to all nations and religions. Gynaecology was then doubly a women’s affair, with female patients but also with a famous female practitioner, Trotula di Ruggiero, known as Trotula of Salerno, who wrote several works in the 11th century (Diseases of Women Before, During, and After Childbirth, Treatments for Women, etc.). An illustration in a medical treatise (Medicina antiqua) shows her (fig. 1) in the centre, administering a remedy based on a plant, comfrey (Symphytum), to a woman suffering from amenorrhea sitting on a kind of stool, whose raised clothing undoubtedly indicates a gynaecological consultation, while on the right, another woman prepares a medicine.

In addition to knowledge, which has been circulating from antiquity to the present day in the form of treatises and correspondence between scholars, techniques and instruments have been subject to a type of globalization that accelerated in the second half of the 20th century.

French gynaecologist Pierre Simon (1925-2008), a pioneer in the approach to painless childbirth and reproductive issues, is an example of a doctor with an international career. Traveling to Southeast Asia, the USSR, and the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, he brought back books, testimonials, and innovative practices. The Pierre Simon Collection at the Centre for Feminist Archives includes several models of intrauterine devices (or IUDs) from the United States, most of which come with their original packaging and a booklet explaining the benefits of their use (fig. 2), as well as correspondence between American pharmaceutical companies and French gynaecologists, introducing them to new methods of contraception. There are also several educational charts that he brought back from his trips to China (fig. 3).

The feminist manual Our Bodies, Ourselves is emblematic of this global circulation. Written by women for women and first published in the United States in 1973, the book was translated into French under the title Notre corps nous-mêmes in 1977. Beyond these two countries, the book has been widely circulated and translated into many languages. In 2016, a new team of French authors decided to produce a completely updated edition, which was published in 2020 by Éditions Hors d'atteinte. The website “Notre corps, nous-mêmes” presents the history of this collective adventure, notably through a montage of covers of the book from different periods and languages (fig. 4). This example testifies to the various forms of globalization produced by people with uteruses, and not only by the medical profession.

Knowledge, medical practices, and healthcare systems have therefore been the subject of intense discussion among scholars, doctors, and patients since ancient times, and on a large scale.

Circulation and globalization around contraceptive and reproductive rights

Globalization is also evident in the demand for contraceptive and reproductive rights. This practice is certainly more recent, dating back to the early 20th century, but it has accompanied waves of feminism. These waves have been remarkable for their ability to connect women from different countries. We see very strong echoes of this in the ultra-contemporary period, for example in the defence of abortion rights in the United States when the Supreme Court challenged the Roe v. Wade* ruling in June 2022. Numerous rallies denouncing this decision took place across the country, in states where legislation immediately became repressive (Missouri, South Dakota, Oklahoma, etc.), but also in states where reproductive rights did not appear to be in danger (Minnesota, etc.). Europe in particular, but not exclusively, witnessed speeches, marches, and demonstrations condemning the US Supreme Court’s decision, starting in June and continuing throughout the summer of 2022. In France, for example, the climax of the protests was a series of demonstrations organized on July 2 in Paris and in some 40 other cities across the country. The flyer (fig. 5) from a collective of trade unions calling for a large march in the capital uses a series of references: Place Pierre Larroque in the 7th arrondissement, near the Ministry of Health and Prevention, is named after the former resistance fighter and “creator” of social security.

The coat hanger and the expression “women decide” are also part of a history of struggles. Finally, the name of the international collective reflects concerns about recent attacks on abortion rights in several European countries (Poland, Hungary, Italy, etc.). In the summer of 2022, debates will begin in France on enshrining this right in the Constitution.

As a symbol of past struggles for access to this right, the coat hanger has been featured in numerous rallies. In Argentina, Poland, and France, it symbolizes the international solidarity that unites women and their right to freely dispose of their bodies. It has been repurposed in two ways: originally used for storage, it became, alongside knitting needles, one of the tools used for clandestine abortions throughout the 20th century, inserted into the body at the risk of injury, haemorrhage, and death. It is brandished as a foil that women no longer want. In 2016, Family Planning launched a media campaign called “Ceci n'est pas un cintre” (This is not a hanger), appropriating the slogan from Magritte's painting, in order to raise awareness of the dangers of clandestine abortions, which caused between 45,000 and 50,000 deaths per year during that decade. Now, hangers are used as visuals to call for militant action (fig. 5), drawn on cardboard or taken out of a wardrobe for a moment, and brandished by women in numerous demonstrations on several continents (fig. 6).

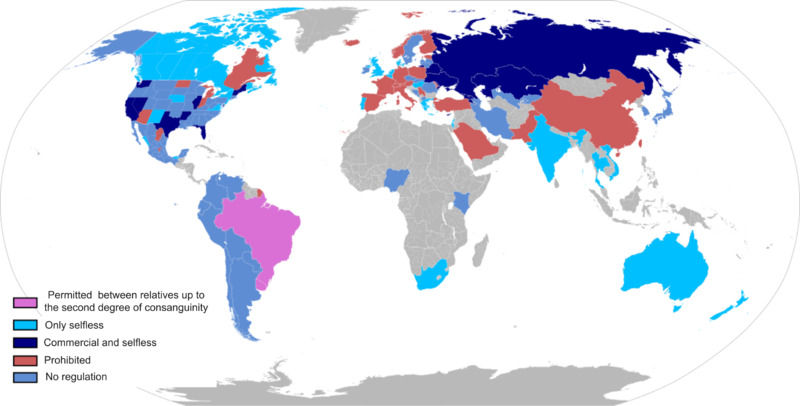

While the globalization of demands initially affected contraceptive rights, in recent years it has also concerned reproductive rights. Medically assisted reproduction (MAR) and, even more so, surrogacy (GPA) are driving people who want to have children to take advantage of legislative differences between countries around the world. By crossing borders and traveling to countries that allow these practices, women and men seek assisted reproduction techniques (ART) or people willing to lend or rent their wombs (GPA). The widely varying laws in force are giving rise to a new type of travel, known as “reproductive tourism”: for example, access to GPA (fig. 6) can vary according to several criteria, including financial status, of course, but also nationality, religion, or sexuality. Even within the same country, laws can differ, as in the United States, where each state has its own legislation. This new form of “tourism” can therefore be national or international.

Within this global landscape, India has long been seen as an El Dorado for surrogacy. This has also sparked debate in the country, with numerous conferences bringing together female politicians and feminists, demonstrating a political will to support and protect surrogate mothers, such as in October 2015 in New Delhi, led by Lalitha Kumaramangalam, chair of the National Commission for Women from 2014 to 2017 (fig. 7). However, since 2018, the law only allows surrogacy for local couples who have been married for at least five years, which has effectively restricted travel to this country. US nationals, who were previously very numerous, have redirected their final destinations, for example to Ukraine, one of the main countries in Europe to allow this practice.

Since February 2022 and the outbreak of war in Ukraine, there has been a proliferation of media reports and articles about couples, surrogate mothers, and babies “stranded” by the fighting. Whether immobilized in the country, crossing borders discreetly, or undergoing veritable exfiltration, several solutions have been explored to deal with the war and its consequences, taking into account the different laws in the host countries. This episode, like others, reminds us of the reversible nature of global movements around the uterus.

Bibliography :

M. Butel, « Les utérus des Américaines à la merci des États », D&L, 199, 2022 (en ligne).

V. Chasles, M. Girer, « Tourisme médical et santé reproductive : l’exemple de la gestation pour autrui en Inde », Revue francophone sur la santé et les territoires, 24, 2016, p. 1-9.

M.-A. Frison-Roche, « La GPA, ou comment rendre juridiquement disponibles les corps des êtres humains par l’élimination de la question », in B. Feuillet-Liger, K. Orfali (dir.), La réalité de deux principes de protection du corps dans le cadre de la biomédecine. La dignité et la non-patrimonialité, Rapport final GIP Justice, 2016, p. 365-382.

S. Hennette-Vauchez, D. Roman, « Du sexe au genre : le corps des femmes en droit international », in E. Tourme Jouannet et al. (dir.), Féminismes et droit international, Paris, Pedone, 2015.

S. Rudrappa, « Des ateliers de confection aux lignes d’assemblage des bébés. Stratégies d’emploi parmi des mères porteuses à Bangalore, Inde », Cahiers du Genre, 56, 1, 2014, p. 59-86.

| Sacralising the organ | An organ of globalization | Violence against the uterus |