Reversing gender roles

Since Antiquity, a woman dressed as a man beckoned an inverted world, dear to humourists. Wearing trousers symbolised power. The more society excluded women (from the public sphere, from teaching, from politics), the more the fear of revenge haunted the imagination of the dominant. Reversing gender roles was an antifeminist fantasy. The 19th century demonstrated this generously, producing politically fictious caricatures in abundance such as these. There were more to be found in the 20th century. The most famous humourists contributed such as Albert Robida (1848-1926), maestro of fantasy illustration and author of a monumental work.

What would happen if these women, led by Hubertine Auclert, armed with vitriol, took power from the “president of the men’s Republic”? If they revolted, building barricades in the vein of “liberty leading the people”, and moreover, fully clothed? What if they played the Pétroleuses, accused of having setting fire to Paris in 1871?

They would give exclusive political rights, indemnity to victims of male “despotism” especially and they would reform female attire.

Here in question, is a masculinisation of an operetta, combining frills (lace, flounce, intricate hair styles for long hair) and masculine symbols (cigarettes, hats, spread legs, arms hanging away from their bodies, canes). In the right foreground, the woman in breeches stands out because of her resemblance to George Sand.

Unusual for this kind of humour, the feminised men are shown in dress, with only the moustaches and beards as a reminder of their once-strong sex.

Wearing the pants

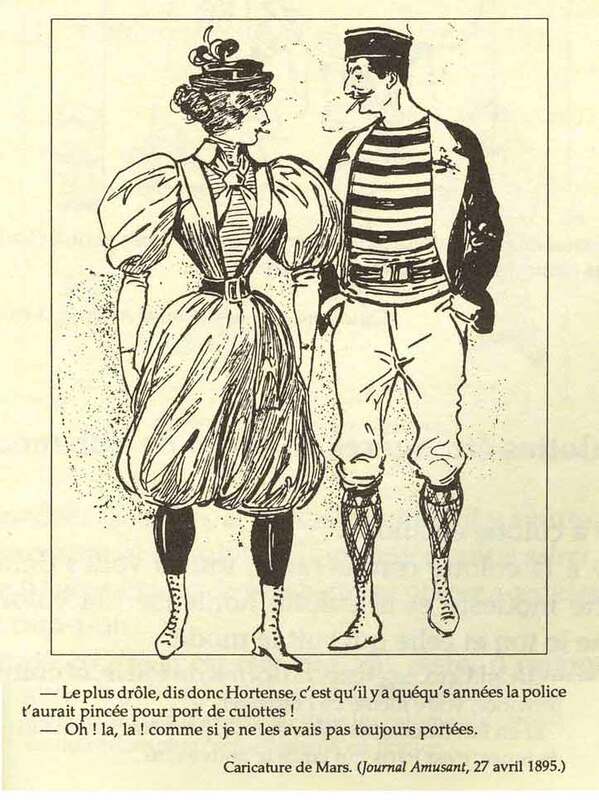

“Porter la culotte” (literally, “wearing the pants”) is a very old expression meaning to have the power, notably in the domestic realm. It is in principle, the man who wears it, but it is more often than not the woman who is on the receiving end of this popular expression, which is constantly being updated.

Therefore, in 1895, cycling fashion inevitably recalled this old affirmation. The dialogue between this couple can be generalised. Haven’t women indeed, always “worn the pants”? This is what is being suggested. Is this even truer in working-class urban environments, where women often play the role of “minister of finance”?

Although this drawing by Mars in Le Journal amusant gives Hortense the pants, it shows a couple in a fairly egalitarian relationship, suggested by the symmetry of the two figures and their outfits. However, Hortense is given a slight competitive advantage, winning on account of her leg and arm spacing and her build (exaggerated by the balloon sleeves), she even outshines her companion stood slightly behind her. What has the man got? A taller stature and a reminder of the law, the aging sword of Damocles hanging over emancipated women. The cartoonist portrays a good-natured version of the aged-old conflict between the sexes, devoid of any real misogyny.

The debate around pants since the Middle Ages…

The debate around pants was quite a banality. The first representations can be traced back to sculptures from the Middle Ages. Their inspiration was misogynistic, showing the unthinkable, what was to be avoided, chaos here evoked by switched objects such as the spindle wheel for women’s use on the floor. Here, she brandishes the spindle wheel, he, the stick. The breeches that the couple are fighting over is a French culotte with a hanging fly. We can determine this image to be from approximately 1810-1820 thanks to the clothes shown (the doll’s empire dress on the left, the man’s breeches).

This image evokes peasant society, rich in proverbs on this subject. “Tiens le pantalon si tu veux la paix” (“Take hold of the pants if you want peace”), (Corsica). “Ni pantalons la femme, ni jupes l'homme” (“Neither pants for women, nor skirts for men”), (Catalonia) quoted by Martine Ségalen. But urban society, whether proletarian or bourgeois, is no stranger to this kind of inversion. The cause of the quarrel? The jealousy of an unfaithful husband, a paycheck spent at the bistro... Woman prevailing over man. There have been many variations, but often, as is here, they are inspired by the principle of “the world upside down”, which explains why, in this “great household quarrel”, the boy and the dog are on the woman’s side, and the cat and the girls on the man’s.

An antifeminist fantasy. Role reversal.

Woman-author, blue stocking, emancipated, free woman, New Woman (“femme nouvelle”), flapper (garçonne) … many a term existed to refer to a character, a “model” more so than a historical reality. This was particularly the case with caricatures which played on distortion, excess, these sources reveal it was the imagination of men, intertwining with ideology, fantasies, fears, attraction, disgust.

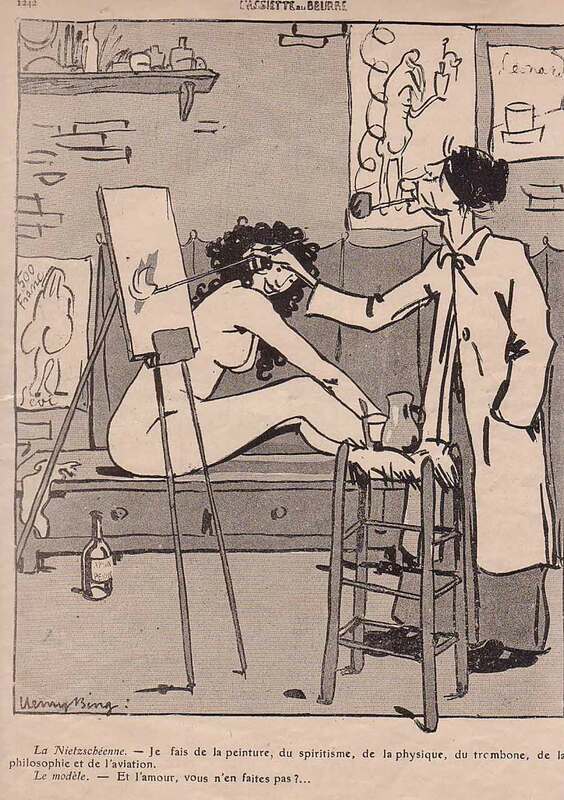

In 1909, the Montmartre native and painter Henry Bing created the She-Nietzschean who personified inversion. Her artist’s smock buttoned up to her neck masks her old rags and a thin, sexless body (due to her lack of breasts). Her bun indicates that she’s a woman, the pipe a certain masculinisation, as does the caption.

The “She-Nietzschean” has all the disproportional, disorganised and compulsive ambitions of a turn of the century “femme nouvelle” (New Woman). Here, these ambitions become the object of ridicule. Her art is summarised by a few smudges hung on the wall. Her musical tastes lead her to a male instrument, the trombone. An unconvincing scientist, she studies physics (an allusion to Marie Curie) all the while leaning towards spiritualism, all the rage at the time. Aviation, still in its infancy, effectively attracted women who made the headlines. Her philosophy earned her the name “She-Niezschean”, a symbol of modernity but also chaos, insanity and instability…

The model-woman is obviously her physical and moral opposite in every way. She raises the question of what’s supposed to be the most important thing in a woman’s life: love. The message was clear. The New Woman would be condemned to voluntary or endured celibacy, her ambitions cutting her off from normal men and women. Masculine women would lose all their seductive appeal.

Inverted from a gender viewpoint, but also in the medical sense: homosexual by taste or by default! Is this not suggested by the scene in which the She-Nietzchean paints female nudes, an indication of a more or less conscious desire? Condemned to ridicule and solitude, alcohol is her left to console her, bottle of pastis lies on the floor.

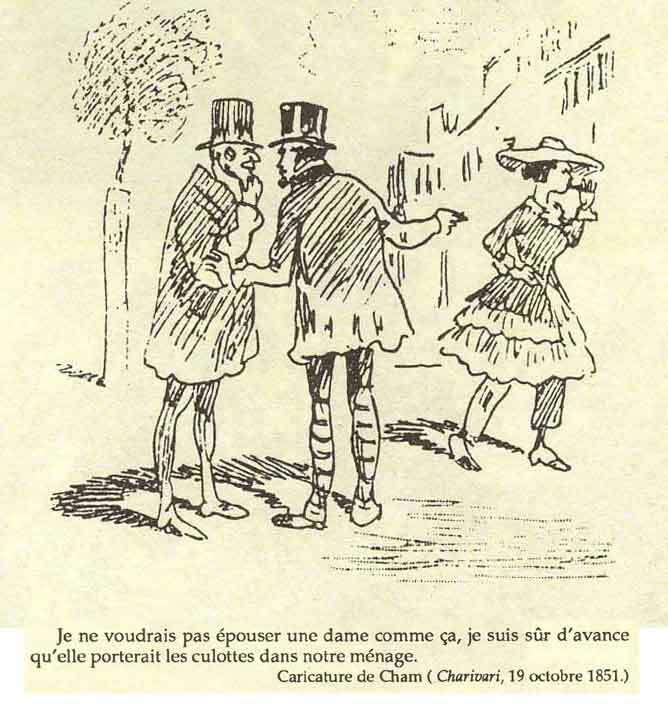

Inversion does not make for happiness… In Le Charivari, in the middle of the 19th century, a regular contributor Cham, made this point just as clearly. Dressed according to Amelia Bloomer’s principles, women would stop appealing to men, convinced that such an attire would indicate a domineering woman. So, there was nothing very original in the reactionary imagination of the cartoonist Amédée de Noé, known as Cham (1818-1879), who drew 40,000 cartoons for the French and British press, including Le Charivari.

Political fiction. The triumph of feminism in 1958

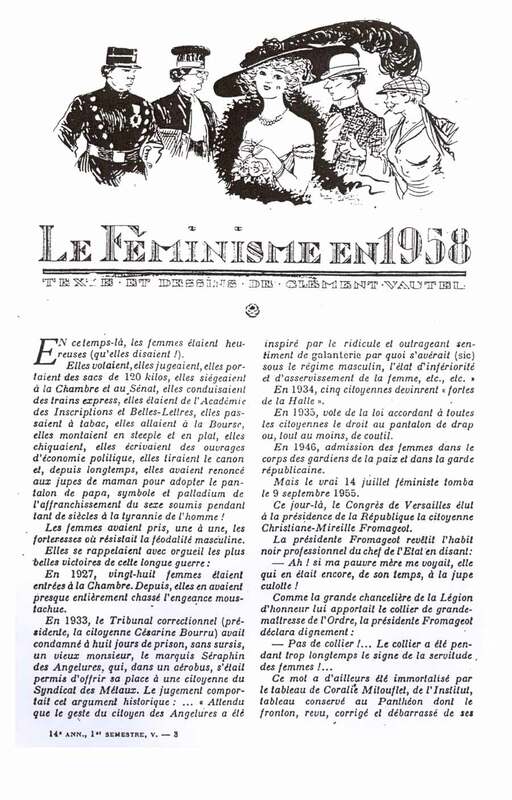

In Je sais tout, a monthly magazine in wide circulation, Clément Vautel imagined in 1918, the triumph of feminism in the year 1958, forty years later. Just as his predecessor Robida did, he pictured a necessary clothing reform. Masculinised women would be the ones to forcefully impose this new uniform.

Feminism here was depicted as a totalitarian movement. Revolutions and regimes strive to achieve their vision of the New Man by, among other things, imposing a specific costume on him. The scenario imagined by Vautel would hardly shock. He was indeed one of the most actively antifeminist journalists. As a so-called “average Frenchman”, he railed against the emancipation of women, while fomenting his anti-Semitic views.

Clément Vautel, a pseudonym of Clément Vaulet (1876-1954), of Belgian origin, was known for his journalism. Author of 30,000 articles, he was also a script writer. He started writing his novels well after forty “to earn a living in his old age”. He was inspired by current affairs, from a satirical point of view. During the interwar period he was a popular success due to his works such as Mademoiselle sans-gêne (“Shameless Mademoiselle”), Madame ne veut pas d’enfant (Madame wants no children), but especially Mon curé chez les riches (Mon priest at the richs’) (record sales for a French novel, one million copies sold) et Mon curé chez les pauvres (My priest at the poors’). In 1941, he published his “memoire of a journalist”, Mon Film (“My Film”) (Albin Michel).

“The dress” by Hubertine Auclert

Hubertine Auclert (1848-1914), at the forefront of suffragism in France and a feminist considered to be one of the most radical of her time, gave her opinion on the dress in the newspaper, Le Radical, to which she contributed regularly (two monthly articles from 1896 to 1909). Here is the article in full.

Hubertine Auclert, “The Dress”, Le Radical, 26th December 1899.

“To the question put to its readers by Revue pour les Jeunes Filles (“Magazine for young girls”): “Are you in favour of reforming women’s costume?”, some young ladies, who were held back by tradition for fear of frightening the suitors to their hand, replied that the dress should be retained. However, these enthusiasts of women’s dresses emphasised its disadvantages so well that they, more than those who abhorred it, disliked it.

One intelligently pointed out that luxurious dresses create impassable castes in the female world, that they are absorbing, cumbersome, and an obstacle to serious occupations.

Another reader spoke out against the incessant need to change, to modify our costumes, to combine new gowns. “At this game,” she says, “not only do we lose time and money but also serious thoughts, and we learn to be frivolous! –So down with the dress? –No!

Unlike Mme Astié de Valsayre, who lobbied deputies for freedom of dress, one correspondent proposed banning women from wearing men’s suits. Her aversion to trousers is more akin to pathology: “I always feel”, she says, “a sense of embarrassment, of painful discomfort when on a pavement I meet a cyclist in culottes...”. Well, when we make the same encounter, we rejoice. Aren’t kind cyclists the harbingers of female emancipation?

Those who are afraid of losing their grace and beauty via a convenient costume suggest that they lack these natural gifts, for beauty and grace, which so irresistibly charm and seduce, need no adornment.

Those who are afraid of losing their grace and beauty via a convenient costume suggest that they lack these natural gifts, for beauty and grace, which so irresistibly charm and seduce, need no adornment.

A subscriber to La Revue rightly points out that there are many women whose active lives do not sit well with bulky skirts. New women,” she declared, “are not the ones who make fashion, and the fashion they don't make, they don't have the courage to brave”. They will have it when they become citizens.

Commenting on this survey by La Revue for young girls, Le Temps said, “Theoretically, the whole of feminism is involved in the question of costume. Should women keep the bulk of skirts or devote themselves to active life? That’s where the problem lies! And the authoritative newspaper, with which we are in complete agreement this time, answers itself, “the real feminists, the uncompromising ones, those who are logical with their principle, are in favour of men’s suits”. Certainly, confrere, since women’s costume, so complicated and paralysing, puts women in a state of inferiority to men.

Le Temps, after admiring the good sense of female correspondents and recognising that women are generally neither revolutionaries nor utopians, (oh what a surprise!), agrees with us. “Who knows,” they say, “if it is not a mistake to refuse them the right to vote, if they won’t introduce a precious element of stability into our politics, which needs it?”

Oh Le Temps! We have said it often enough for you to know, with women will enter reason and order into the administrative and legislative assemblies, the enemies of the provisional twelfths.

How much easier it would have been for women to enjoy civil rights if their dress had not been so different from that of men! What makes women unequal to men is not their intelligence, but their dress.

Inevitably, women's dress will change, because how can you wear it without a corset? Our neighbours have already outlawed this instrument of torture. Mr. Leygues would no doubt not be blamed if, following the example of the Romanian Minister of Education, he sent a circular to the heads of girls’ boarding schools forbidding their pupils to wear corsets.

One of the most recent women to receive a doctorate, Miss Tylicka, devoted her thesis to this high-pressure machine, the corset, which compresses the most important organs, pushes the ribs inwards, causes respiratory problems and brings on anaemia and chlorosis. With the elimination of the source of so many ills, the extravagant skirts will fall into disuse.

Many women have adopted men’s attire. Rosa Bonheur was one of them. “I wear breeches”, she wrote, “and find this costume completely natural. Nature having given us all two legs, I don’t understand why working women in particular should not be more comfortable and more properly at ease, having two sleeves at the bottom, for trotting through the mud and riding in cars. I hope that this will become fashionable, to the great dignity of our species, and that we will reserve the sovereign skirt for the drawing room, so that everyone can see her skin as well as her husband’s.”

In fact, despite the fact that Mr. Le Bargy has freed men from the habit of wearing a frock coat to get married, women still cling to the evening dress, the low-cut dress.

It would be a pleasure for the eyes to see a lot of the fresh skin of supple, young bodies. Unfortunately, bosoms and shoulders only show themselves well when they have much matured and when it would be teasing to conceal them, so as not to provoke realistic remarks such as the one made recently in a salon by a gentleman who, looking at a pitiful fifty-year-old woman in a low-cut dress, said to his friends. “I can't see the bosom of Madame X... without thinking of the spoiled meat of a stall!”

All it would take is for a few socialites to have the sense to wear a dress that covered cleavage in the evening for the fashion to be adopted. Between the sort of dress and the frock coat, the advantage goes to the latter. Who would dare to argue that a dress, whether low-cut or not, would suit Mrs. Dieulafoy as well as her morning coat?

Free men have standardised their simple costumes. Those who dream of becoming their equals cannot claim to retain the artifices of slaves, the anti-egalitarian luxury that can only be acquired at the expense of freedom.

To be able to live independently from man, the French woman must not only increase her resources, she must also reduce her fictitious needs.”

| Differentiating | Reversing gender roles | Autorising |