Differentiating

The differentiation of appearances according to one’s sex is a fundamental law. Since Antiquity, political and religious authorities have been keeping a close watch over it. Differences expressed through clothing— a cultural fact, seems justified in nature by anatomical differences, exaggerated by scientists. This is the result of early conditioning that prepares adults to be for the “destiny” of their gender.

In the 19th century, this differentiation intensified: trousers, the closed garment, became the norm for men in the 1820s. They adopted a simple, practical, and austere attire. During the Revolution, the « sans-culottes » initiated this major evolution in clothing. The skirt and dress, open garments, were imposed on women with new constraints for those who followed the fashion of crinolines and especially corsets. The female attire was even more open as it was worn without undergarments, or with open drawers.

This radical differentiation in appearances coincided with the Napoleonic Civil Code (1804) which established the modern patriarchal family model. Women’s situation regressed in every domain of social life, provoking perennial feminist contestation, seen even to this day. This is why the clothing reform had such a profoundly political dimension to it.

Why “the habit doesn’t make the nun” [1], by Nicole Pellegrin

The adventure of Jeanne Baré, crossing seas for over a year without ever revealing her sex, is one of the most thrilling anecdotes of “transvestism” during the Ancien Régime. Historian Nicole Pellegrin presents the now-famous case of the first woman to have circumnavigated the world with Bougainville’s expedition. She shows us the extent to which male or female appearance is a cultural reality.

Nicole Pellegrin, « Le genre et l’habit. Figures du transvestisme féminin sous l’Ancien Régime », Clio, Histoire, femmes et société, n° 10, 1999, p. 43:

“The case of Jeanne Baré is […] exemplary insofar that she was a servant (and maybe a mistress) of one the of naturalists of Bougainville’s expedition, she managed to hide her female identity until the arrival of vessel Étoile to Tahiti, the island of Cythère, on the 28th of May 1768. “Mr. Commerson had gone ashore with Baré, who followed him carrying weapons, provisions and plant notebooks with the courage and strength that had earned him the name of our botanist's beast of burden. No sooner was the servant on shore than the Cytherians surrounded him, shouting that he was a woman and wanting to do him the honours of the isle. The officer on guard had to come and free him”.

This story is edifying in more than one way. The Tahitians, less inhibited by the concept of identity created in the West by gendered appearances based on dress, were more perceptive than the European sailors. Despite the suspicions of some and the frightening promiscuity on board ship, Jeanne Baré fooled her compatriots for at least two reasons. She knew how to fish with her breasts tightly bound, but above all, she belonged to a society, the Ancien Régime, that believed in the coincidence of appearances versus reality and asserted that “the habit makes the monk” indeed. When questioned by Bougainville, Jeanne Baré was able to touch the latter's heart when she confided in him the reasons— the most avowed, for her embarkation, “born in Burgundy and an orphan, the loss of a lawsuit had reduced her to poverty, [...] she decided to disguise her sex [...], moreover, she knew when she embarked that there was talk of sailing around the world, and this voyage piqued her curiosity”. Bougainville himself confessed his admiration and asked the Court for indulge this “wise” 25-year-old, who was “neither ugly nor pretty”. Unlike Commerson, ignominiously disembarked before the end of the circumnavigation, Baré had a happy ending, married to an officer garrisoned on the Ile de France, she received a royal pension of 200 French livres in her old age. Without a doubt, like the “chevalier” Baltazar and the hundreds of female soldiers who enlisted in European armies from the Ancien Régime onwards, “she figured that a powerful subject of love, interest or glory had forced her into this disguise” and could justify it in the eyes of all as well as in her own eyes”.

>> More on Jeanne Baré, Sylvie Steinberg, « Jeanne Baré, aventurière et travestie », Lunes, n° 20, juillet 2002, p. 41-49. Sylvie Steinberg is the author of a major thesis on the cross-dressing intitled La confusion des sexes. Le travestissement de la Renaissance à la Révolution, Paris, Fayard, 2001.

Naturalising gender differences

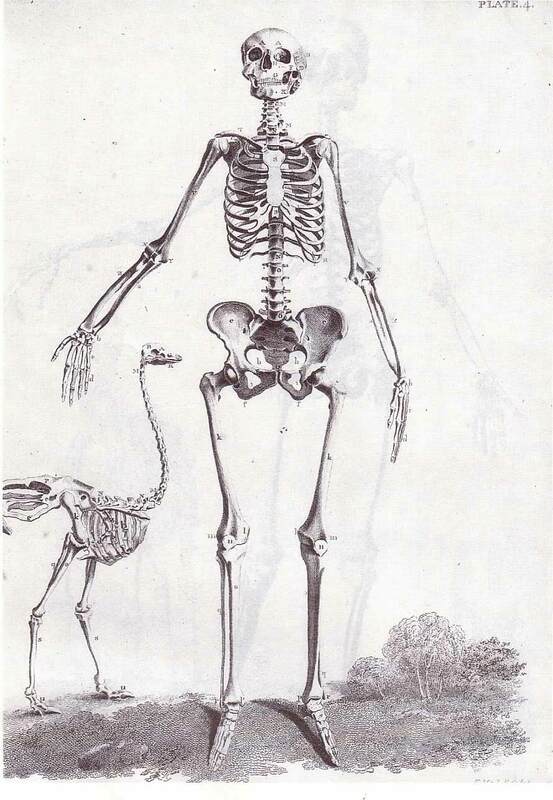

For scientists, sexual difference was not merely limited to genitalia. Each body was sexed according to a principle of “hierarchical differentiation” that began to prevail in the 18th century. It was up to anatomists to demonstrate these differences through presentation tricks and the use of non-representative skeletons.

Figure 1, a man’s skeleton in John Barclay, The Anatomy of the Bones of the Human Body, Mitchell and Knox, Edinburgh, anonymous, 1829, © private collection.

Comparative table of the two anatomical representations: Male/Female:

|

|

Male |

Female |

|

Skeleton |

Tall in stature/Large head/Normal neck/Normal skull/Narrow pelvis/Large thorax/Big bones |

Small in stature/ /Small head/Long neck (phrenology = absence of passion)/ Metopic skull/Broad pelvis/Narrow thorax/Frail bones |

|

Choice of posture |

Shown slightly in profile/ Gaze direction: upward/ Symmetrical legs: ability to move |

Shown from the front/ Gaze direction: downward/ Symmetrical legs: statics, stability, conservatism |

|

Decor |

Manor/ civilisation |

Trees/ undomesticated nature |

|

Animal analogies |

Horse: fast, powerful, hardy, noble mammal Shown from the front: enlarged head and chest = powerful |

Ostrich: bird reputed to be stupid and timid Shown in profile: huge pelvis and tiny head = fragility |

|

Conclusion |

Perfect sex, strong sex |

Imperfect sex, weak |

This would be the vision to prevail in anthropological learned societies that flourished in the second half of the 19th century. They disseminated the idea, defended by Broca, the founder of French anthropology, of the intellectual inferiority of women. Gustave Le Bon, founder of social psychology, further developed this sexist conception (1879).

Barclay’s skeletons

This representation, in wide circulation and commented on in the history of sciences, was the work of a Scottish anatomist, Barclay. It calls to mind the first female skeleton represented in 1759 in the Treaty of osteology, drawn by Marie Thiroux d’Arconville (under the male pseudonym of Jean-J. Sue). This female skeleton was small, the width of the pelvis exaggerated. The metopic suture which seems to separate from the frontal bone, is a rare anomaly in women (as in men incidentally). The aim was to show radical sexual dimorphism. This marked the end of the unisex model commented on by the historian Thomas Laqueur.

This was the hierarchical vision which established itself. The naturalist, Julien-Joseph Virey (1775-1846) gives a canonical version in his Natural History of Man (1800):

“The upper parts of the man’s body, such as the chest, shoulders and head, are strong and powerful, the capacity of his brain is considerable, and contain three or four more ounces of brain according to our experiments, than the skull of the woman [...] In the woman, on the contrary, the head, shoulders and chest are small, thin and tight, while the pelvis or hips, buttocks, thighs and other organs of the lower abdomen are ample and broad. Man is thus designed for thought, woman for reproduction”.

To Virey, women were naturally “inferior” and “feeble” but the perfect “reproductive sex”. This is how biology mingled with philosophy and moral, laying down the foundations for social order. It is worth noting that this ideology was contemporary to the civil ban of 1800. Social regression was on the horizon for the “weaker sex”.

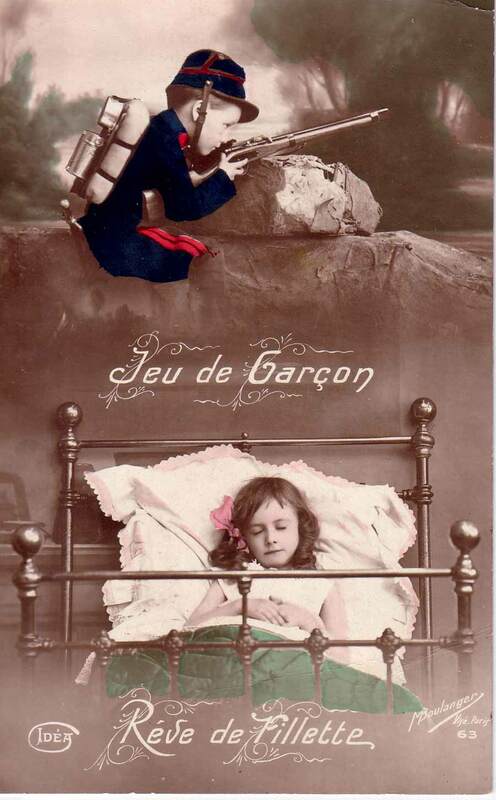

Conditioning: the dreams of girls and boys?

Gender differentiation is the result of early teachings. At the end of the 18th century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a reference for progressive circles, distinguished himself as an educational model in his treatise, Emile. He presents us his plan for Sophie: “Women’s whole education must be relative to men. To please them, to be useful to them, to be loved and honoured by them, to bring them up young, to care for them when they are old, to advise them, to console them, to make their lives pleasant and sweet: these are the duties of women in all times, and what they must be taught from childhood”. Rousseau’s influence would become apparent in the long term.

This type of postcard dating back to the First World War (1914-1918), illustrates sexual difference in childhood in a caricatural way. The absolute passiveness of the little sleeping girl stands in stark contrast to the activity (by excellence) of war. These future social roles are resolutely articulated around the complementarity of the concepts of protector/protected. The context of war accentuates the imperative nature of this role distribution which also corresponds to ideological and strategic concerns. The conditioning, or brainwashing, addresses itself to adults, this card will appeal to them (a certain nostalgia for the age of games) and confirm their conviction that there is a distinct natural destiny for each sex. It also concerns children who aren’t completely spared of “all-out” war.

These early conditionings coincide with revolts, equally as early, such as those of the feminist Madeline Pelletier. “When, in my childish ambition, my head filled with stories of tales of France, I used to say that I wanted to be a great general, to which my mother would scoff and dryly say, “women are not militaries, they are nothing at all, they marry, do the cooking and raise children”. Madeleine Pelletier would prove her mother wrong…

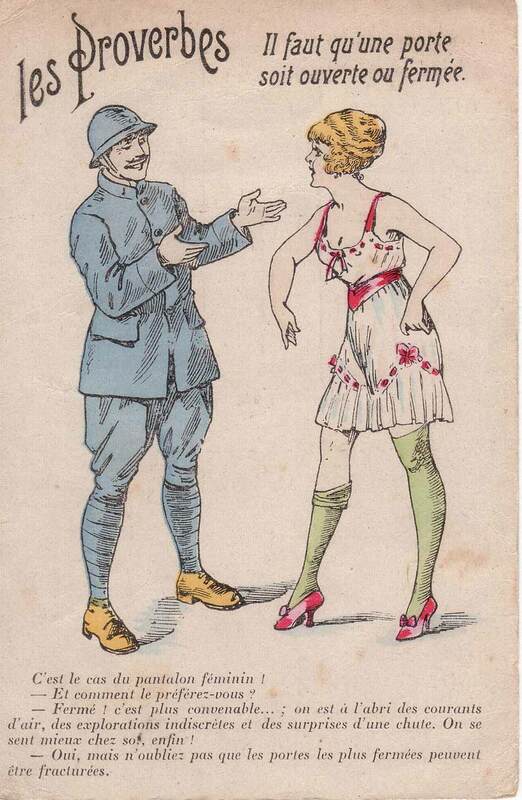

“A door must be either open or closed”.

For a long time, “le pantalon féminin” (women’s pants) would be taken to mean “la culotte de dessous” (underwear). Up until the beginning of the 20th century, these were open and this postcard bears witness to the shock that the transition to closed underwear caused. Like men’s pants, closed underwear were protective. More discreet, they marked an important point in women’s emancipation. “My body belongs to me” is reminiscent with this clothing evolution.

In evocative terms, the young woman represented on this racy postcard summarises the protective advantages of closed underwear: “You feel better at home!”. The hygienists agreed with this statement as open breeches were a good breeding ground for germs. The moralists believed that closed breeches were more appropriate before marriage. Say goodbye to the open breeches that have obsessed so many gentlemen!

The aroused solider makes it understood that no woman is safe from male lust. The affirmation “even the most secured doors can be broken down” is threatening. This invasion evokes the possibility of rape, and no doubt the possibility of a brutal deflowering. The soldier who gets the last word, prefers doors—that’s to say, underwear and women, open. The illustration accentuates the text, adding menace when confronting the over-dressed soldier in a helmet, and the skimpily clad woman (a young and naïve, woman of easy virtue, “emancipated”). Their gazes never meet announcing an unequal exchange; she speaks to him looking him straight in the eyes, he responds, his eyes lowered in the direction of her assets. He literally “gets an eye full” (se rincer l’oeil, an expression from the period). Her lowered stocking suggests in any case that it won’t take much longer for the “door” to open or to be opened.

| Prohibiting | Differentiating | Reversing gender roles |