A world unto itself

The subject of all kinds of preconceived ideas and fantasies, the uterus is one of the organs most conducive to the emergence and circulation of atypical theories. One of the reasons for this is undoubtedly the mystery it has long held for men who consider themselves experts on the female body and this womb, which they themselves do not possess. Whether fantasized or real, there are many reasons to consider the uterus as a separate entity, making it a veritable world unto itself.

An organ so autonomous that it is mobile

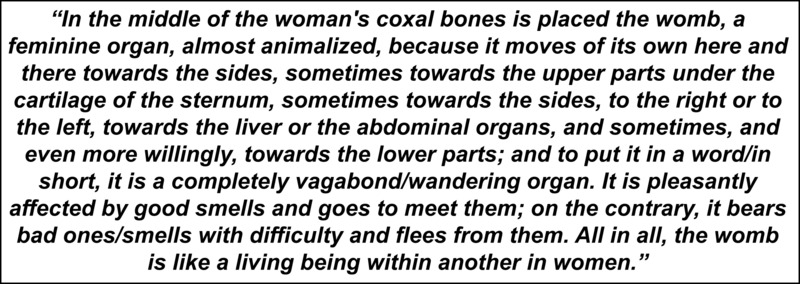

Doctors and philosophers of Greco-Roman antiquity (Hippocrates, Plato, etc.) very early on attributed special properties to the uterus, making it an entity that influences women’s health and behaviour. Aretaeus of Cappadocia, author of a medical treatise, On the Signs and Causes of Acute Diseases, writing in Greek in the 1st or 2nd century AD, described it as “a living being within another.” Like other colleagues of his time, he claimed that the uterus was mobile and travelled within a woman’s body according to circumstances and completely independently of her will (fig. 1). This tendency had already been described several centuries earlier by Hippocratic physicians, who believed that the womb could migrate within the body depending on its heat and humidity, but also on odours, thus causing health problems. When dry, the uterus moves in search of moisture, which is believed to be beneficial. The medical literature of the time contains numerous gynaecological remedies, potions, and pessaries* made from strongly scented substances intended to return the organ to its place and thus cure the patient. It was also during this period that hysteria came to be understood as a disease caused by the wandering of the womb (see the notice “An organ that is still vulnerable even today?”).

For some authors of the 2nd century AD, such as Soranus and Galen, although the organ is mobile, its movements are restricted to the abdominal cavity, as it is held in place by ligaments that give it the appearance of an octopus. This refers to the moisture of a hydrated womb, which can move thanks to its tentacles when it becomes dry. This aspect, combined with that of a medical suction cup, can be found on an intaglio from the 2nd-3rd centuries AD used as a protective amulet for pregnancy (see the notice “(Un)cover this uterus that I ought not see”). The tentacled suction cup symbolizes the uterus at the center of a magic circle formed by an ouroboros, a snake biting its own tail, overlooking a key whose teeth can be used to open or close the organ, preserving or releasing its precious contents. These considerations about the wandering uterus persisted for a very long time. Thus, at the beginning of the modern era, Ambroise Paré, a renowned surgeon and anatomist, still gave credence to this belief. It remained shared by part of the medical profession until the 19th century.

A sensitive organ: the site of first sensations

Although it is not the capricious, autonomous, wandering little animal depicted by ancient physicians, the uterus is indeed a world apart within the body. Modern medicine has shed light on some of its long-unknown properties and characteristics. As the first place of habitation for human beings, it is also the place of their first discoveries. It is in the womb that future babies experience their senses.

Studies on foetal life analyse the stages of development of the sensory organs. Chronologically, touch is the first to manifest itself. From the fourth week of gestation, the embryo is equipped with certain receptors specific to this sense, which develops throughout pregnancy, making it sensitive to touch. Later on, it can even sometimes be seen on ultrasound scans sucking its thumb or stroking its face. From the eleventh week onwards, the foetus is able to taste the food eaten by its mother. Using a Doppler ultrasound scan (fig. 2), it is possible to show the circulation of amniotic fluid (here in blue) in the foetus’s nasal cavities and mouth using colour contrast. The foetus can distinguish between the main flavours: sweet, salty, bitter, and sour. The same is true for smell. Since the 1980s, research has focused on the conditions for acquiring the sense of smell during embryonic and foetal life, initially in animals. In the late 1990s, this ability was demonstrated in utero in humans. A very recent study, published in September 2022 and conducted by British and French researchers, even showed that foetuses react differently to tastes and smells. An experiment involving pregnant women eating carrots or kale revealed different reactions in their offspring, as observed using 4D ultrasound. foetuses that had ingested cabbage showed tearful expressions, while those exposed to carrots displayed smiling faces on the medical imaging scans.

Hearing begins in the womb around the twenty-sixth week of pregnancy, with the foetus first perceiving the sounds of the body (heart, digestive system, etc.) and then certain sounds coming from outside. Finally, sight appears. Around the seventh month, the foetus’s eyelids open, but it can only distinguish shadows or bright points of light. The uterus is then perceived as a wall or a boundary, a zone of contact between the inside (the foetus) and the outside (the sensory world).

A fantasized place to live

This primitive cocoon has long been considered a safe and reassuring environment that individuals in search of well-being would seek to rediscover, even fleetingly. The Utroba Cave in Bulgaria, also known as the “womb cave,” which dates back several centuries before our era (fig. 3), shows this ancient fascination with the organ and its potential as a “refuge.” Originally a simple natural fault, it is said to have been enlarged by the Ancients. Its entrance, with its unusual vulva-like appearance, gives the impression of being able to penetrate deep into the body to the uterine cavity. The altar discovered inside suggests that it may have been used as a fertility sanctuary at various times. Even today, infertile couples visit it in the hope of being able to conceive after their pilgrimage, aided by the aura of this place considered magical.

This idea of a “womb habitat” is found in other sources. For example, a 10th-century manuscript, a copy of a gynaecology treatise by Soranus (2nd century), adapted and translated by Mustio (6th-5th century), contains a series of illustrations: one of them (fig. 4) shows four wombs, each filled with a future individual represented as a homunculus*. This phenomenon, common in Christian iconography, clearly illustrates the consideration of the uterus as a fantasized habitat.

The very contemporary era has undoubtedly pushed this representation to its peak. Installations and devices of all kinds are proposed in order to rediscover the protection and well-being supposedly reigning in this primary habitat, with artists and creators taking up the issue in particular. One thinks of the temporary installation, Hon, proposed by Niki de Saint-Phalle, Jean Tinguely, and Per Olof Ultvedt at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1966. This imposing sculpture, embodying a “pagan goddess of fertility,” took the form of a huge pregnant woman lying on her back: visitors could enter it through her vagina and then reach her womb. Furniture designers also did not hesitate to create objects evoking such an environment, such as the Finnish designer Eero Saarinen, who, in 1948, at the request of one of his friends, created the Womb Chair (fig. 5). The chair, designed to offer the greatest possible comfort, allows its occupant to relax completely, perhaps reminiscent of the sensations experienced in the womb. These inventions seem to have inspired others in the field of accommodation and relaxation, as we have recently seen a proliferation of hotels and spas offering to welcome their customers into a womb-like environment. Rooms or relaxation areas are designed to metaphorically welcome people into a womb, considered the ultimate place of comfort and well-being.

This idea of the womb as a habitat was explored in 2022 as part of the “Utérus & Co” project supervised by Céline Ader, an art teacher at La Villemarqué middle school (Quimperlé, 56). The students in a fourth-grade class designed an artistic production based on a visit to an artificial womb company in the year 2119. In this fictional world, the reproductive function is outsourced "to liberate the body.” Between fantasy and dystopian poetry, this installation-performance raises a number of ethical and political questions: the invisibility of miscarriages and abortions, the fragility of reproductive rights, and the constraints and assignments associated with having or not having a uterus. A performance was presented in October 2022 at the University of South Brittany. Walking through the aisles of an amphitheatre (fig. 6a) allowed the audience to discover different types of artificial wombs, presented as products for sale by the young artists. In Jeanne P.’s work, entitled Utérus le nid (fig. 6b), one or two foetuses can remain in gestation for twelve months, and thus be born already able to speak. “This nest” is autonomous, yet welcoming.

Finally, the desire to return to the original state and to the womb can even be found in the treatment of bodies after death. Indeed, since prehistoric times and even in Antiquity, it is not uncommon to find the graves of young children known as enchytrised. This term refers to the practice of burying the bodies of young deceased children in a ceramic container (amphora, vase, pot, etc.). For example, the interior of a large amphora (fig. 7) discovered during archaeological excavations in Himera (a Greek city in Sicily) contains the remains of a newborn baby, accompanied by a small vase as an offering. The site of Astypalaia in Greece has yielded an exceptional collection of burials of this type (more than 2,750) dating from 850 BC to the Roman period. The meaning of this rite is explained in the texts. The vase plays the role of the womb, returning the child as a symbol to the environment it recently left.

Bibliography :

V. Dasen, « Métamorphoses de l’utérus d’Hippocrate à Ambroise Paré », Gesnerus, 59, 2002, p. 167-186.

V. Dasen, « Un animal dans l’animal », Revue des Deux Mondes, mai 2005, p. 91-100.

B. Schaal, « À la recherche du temps gagné. Comment l’olfaction du fœtus anticipe l’adaptation du nouveau-né », Spirale, 59, 3, 2011, p. 35-55.

B. Ustun, N. Reissland, J. Covey, B. Schaal, J. Blissett, « Flavor Sensing in Utero and Emerging Discriminative Behaviors in the Human Fetus », Psychological Science, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221105460.

| An organ that is still vulnerable even today? | A world into itself | Sacralising the organ |