The uterus, a male organ?

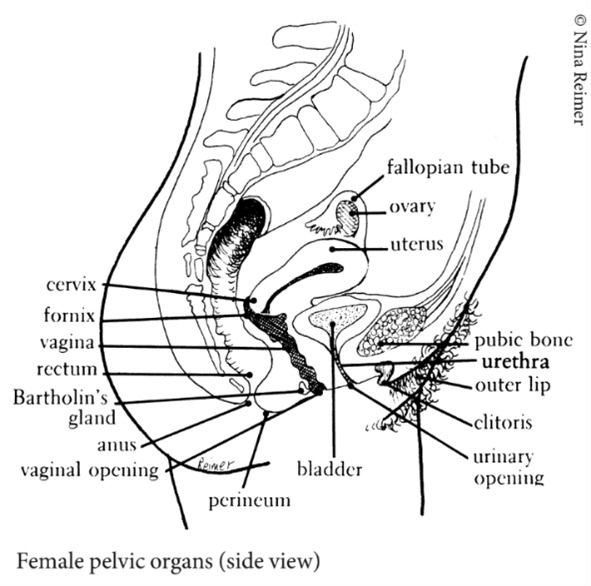

Biologically an organ found in female mammals, the uterus plays an important role in the reproductive process. In humans, the uterus, which is pear-shaped, is located above the bladder, in front of the rectum, and is held in place by a set of ligaments; it is approximately six centimetres high and five centimetres wide (fig. 1). Although still commonly associated with women and considered one of femininity’s attributes, like the breasts or clitoris, for example, it is nevertheless an eminently social organ. The various notes in this exhibition focus on this tension, opting for a social, cultural, and historical reading of the uterus.

For several decades, the body has been under study by humanities and social sciences, which take an essentially global approach, emphasizing the whole over the parts, or organs.

It is also analysed primarily through what it looks like—the surface—and what it can do—its mechanics. Internal organs, which are less visible, have largely been left out of research. Studying them is tricky because it is hard to understand them beyond the functional meaning assigned to them by their etymology: organon, meaning “instrument, tool.”

This exhibition chooses to tackle this difficulty by emphasizing representations of the uterus as a “part of the body” over those emphasizing its reproductive function.

Hidden, concealed, and difficult to access, the uterus has historically been sacralised and fantasized about in many cultures and geographical areas. It therefore presents the paradox of an organ that seems, a priori, to be the standard-bearer of femininity, but over which it is primarily those who are biologically deprived of it who arrogate rights to themselves. The right to know and care for it, through male monopolization of the sphere of knowledge.

The right to possess it and regulate its uses, politically and economically. The right to mistreat it, as shown by the systemic nature of the suffering inflicted on the organ, and more generally on the bodies that carry it, under the guise of care. The right to discuss it and produce images of it. As exemplified by this wax model (fig. 2) showing a C-section: it was on display until the mid-20th century in the museum that Pierre Spitzner set up in Paris in 1856 to spread anatomical knowledge and information about venereal diseases*. The woman giving birth is awake, with her feet tied and her arms held behind her head. Surrounded by her obstetricians' male hands, her open belly displays a uterus controlled by men.

The exhibition’s guiding principle thus primarily questions the evolution of representations of the uterus, their gendered nature, and the dynamics of appropriation and reappropriation by those who produce them. By giving diachrony a prominent place within each thematic entry, this exhibition seeks to reveal the continuities and changes in socio-historical discourse and provide considerations about this organ. It offers a journey through the centuries, even if not all periods are equally represented. From a geographical point of view, the notes focus mainly on Western contexts; occasional forays into other areas invite further reflection on other times and places.