Seducing

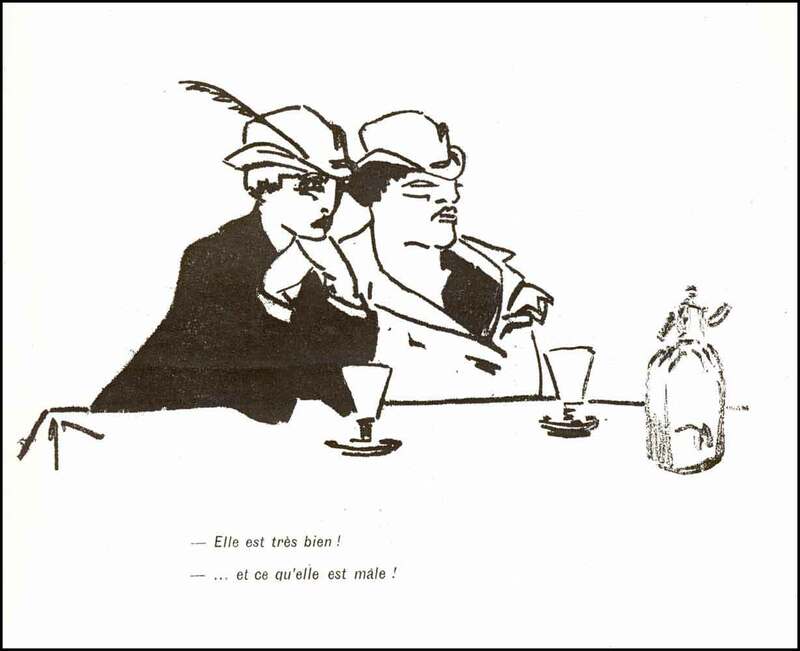

In Paris, from the end of the 19th century, tearooms were a place for rendez-vous with certain cafés also serving as meeting points for women. In the foreground, a woman dressed in male clothing, adopts a masculine posture, an arm stretched out from her body embraces the chair. In the background, gender complementarity is played on in the form of a couple made up of a woman on the right, posing masculinely, and a woman on the left, femininely. The two are drawn together by a gesture typical of modern amorous seduction: lighting someone’s cigarette. The caricature is discreet, but the documentary value of the drawing seems solid. The seated position of these ladies does not reveal their skirts, which they very rarely take off. The cartoonist, Chas Laborde, is not ill-intentioned; this caricature makes you smile, like the whole issue on “mesdam'messieurs” in L'Assiette au beurre, the famous satirical newspaper of the Belle Epoque.

What we might call, for want of a better term, “lesbian masculinity”, dominates the more or less fantasised representations of “tribades” (so, for forensic medicine, it’s a sure sign); a practice that existed in both affluent and working-class circles.

Homophobia had a paradoxical effect: on the one hand, it exposed women who had until then, enjoyed relative social invisibility, to punishment; on the other, it crystallised the awareness of belonging to a particular social group and gave rise to a movement of assertion that involved, in particular, the language of appearances. Cross-dressing played a part in the construction of the modern lesbian identity.

Lesbophile/phobic représentations

Hostility towards cross-dressing is closely linked to homophobia. Cross-dressers were often suspected of being homosexuals. At the turn of the 19th and 20th, a whole body of literature disseminated its obsession with sapphism, portrayed as a perversion, motivated by the hatred of men, associated with sterility and demographic decline, and all the more threatening when exhibited in broad daylight in the public sphere.

The image of the cross-dressing woman was also the medical one circulated by psychiatrists who developed the notion of sexual inversion, which they associated with adopting the appearance of the opposite sex.

In 1912, this drawing from L'Assiette au beurre also shows lesbians at a café. Some twenty years earlier, the cartoonist Jean-Louis Forain had already depicted lesbians in jackets and skirts frequenting a Montmartre café, Au rat (drawing published in Le Courrier français, 14 December 1890).

Lesbian masculinity: an equally popular practice

There is very little documentation of working-class lesbians from the time. Hence the interest of the description of the transformation of “la belle Viviane”, found on the back of a postcard dated 1925:

“I have some news for you. Yesterday, Saturday afternoon, I received a visit from the beautiful Viviane. But you know, I’m still not over it. Would you believe it, she was with a tart… Viviane was dressed like a man, with her hair cut short like a man’s. She had a black suit, a navy-blue terrycloth overcoat, patent shoes and grey gaiters. Quite a man: a blue beret and a cigarette in her mouth... Talk about an entrance! The two of us, Pauline and I, were in the shop and we were like two idiots. You know, I still can’t believe it. She told me: here’s my woman. She told me she was going to come back and see me... She tried to feel me up, but I was on my guard. She told me that her woman thought my eyes were beautiful. Can’t you see that...” (Unfortunately, this postcard ends here).

| Creating (yourself) | Seducing | Working |