Revolutionising

Trousers, a tunic, no corset, no décolleté: this was the “free woman” as dreamt of by the Saint- Simonians of the 1830s. A revolution in dress that amused the caricaturists but which had little effect on the street.

However, this utopian spirit was also to be found in the radical feminist wing of the Third Republic. In 1887, Astié de Valsayre asked members of parliament to “eliminate the routine law prohibiting women from wearing men’s clothing” in the name of decency, hygiene, and simplicity. For the first time, the ordinance of 1800 was officially challenged. In 1891, feminists launched a manifesto in favour of wearing culottes.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Madeleine Pelletier (1874-1939) revived the struggle, enriching it with a genuine socio-historical analysis of the oppression of women. She rejected what was commonly known as “femininity”, including dress.

Dr Pelletier used to dress in an ordinary men’s suit, with short hair, a bowler hat and a walking cane. In the street, she was often taken for a man. In her, the opponents to women’s emancipation saw the confirmation of their prediction: feminism leads to the virilisation of women, and therefore to the indistinction between genders.

Whether uncompromising or conciliatory, feminists, if not through their dress at least through the way they were portrayed by others, played a role in the process of masculinising appearances. On the eve of the war, even a moderate feminist like Jane Misme recognised that “the skirt, symbol and instrument of the inequality of the sexes, remains a fetish that could not be touched without causing a scandal”. The “new woman” dared to cause such a scandal.

Utopias

Twenty years before bloomerism, French utopian socialists reflected on the influence of dress on behaviour and designed a sensible costume for the “free woman”. This costume, known to us thanks to Maleuvre’s engraving, was never worn. It was too radically new to be embraced. Its resemblance to Amelia Bloomer’s design around 1850 is striking.

The Saint-simonian woman

For its time (1832), this costume was shockingly masculinising. The Saint-Simonian woman wears a pair of pants, hidden by a tunic. The pants are embellished with lace, the waist tightly constricted by a belt. The young woman places a confident hand on Saint Simon’s opus. The latter was not the creator of the “free woman”, even though he acknowledged in his later years that “man and woman make up the social individual”. But from 1829 onwards, his disciples developed a genuine feminist theory although the word was still inexistant.

Father Enfantin wanted to rehabilitate the flesh and prepare for the advent of the woman-messiah. “I believe in the coming regeneration of humankind through the Equality between men and women”, he wrote. In 1883, “the companions of women” went in search of the messiah in the East. This movement attracted hundreds of women taken with freedom and social justice (Claire Bazard, Eugénie Niboyet, Claire Démar are among the most well-known), but they did not dress like Saint-Simonians. The influence of Charles Fourier, who Father Enfantin read attentively, is to be found in the utopian dress depicted here. For him, education should make no distinction between the sexes, including in terms of dress.

Owenists and Bloomerists in the United-States

This humoristic cartoon was part of a large series published by the European and American press on Bloomerism. It depicts the difference between the American style and the French style of masculinising dress codes. The French changed the top, the Americans the bottom. Trousers remained a supreme taboo for French women.

As early as 1825, Robert Owen, a disciple of Saint-Simon and founder of the New Harmony Community in Indiana, proposed a radical dress reform taking the shape of the pants and tunic combination. The majority of the women in the socialist community despised and refused this new dress however. It is interesting to note that it was a man who instigated the dress reform movement which was not well received by women.

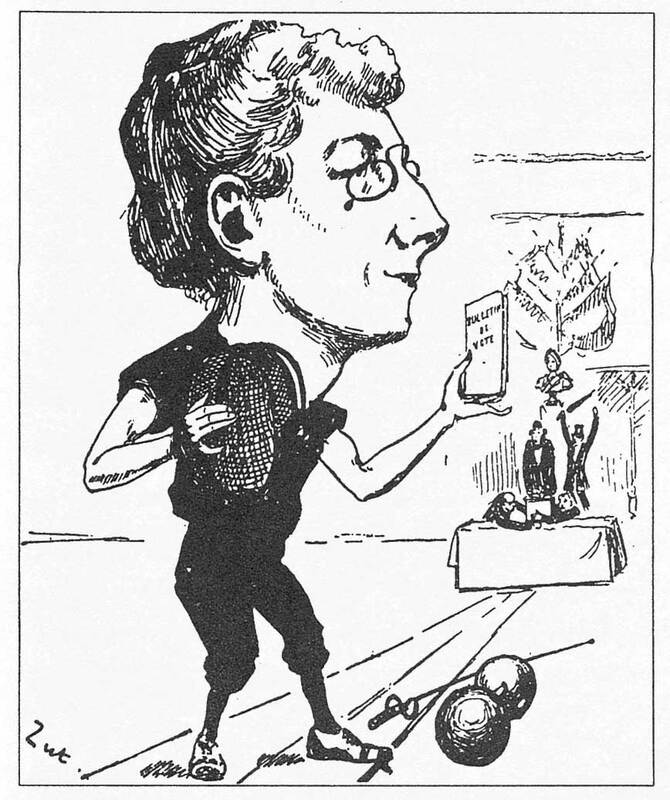

Astié de Valsayre

Marie-Rose Astié de Valsayre (who like to be called by her family name, “Astié”, considered a virile practice), was one to the apostles of masculinised feminine attire. Born in 1846, she studied medicine and earned a living writing for newspapers under her own name or a pseudonym. At the end of the 1880s, she doubled her feminist initiatives, stsanding for the 1889 elections, running a gymnastics class at a secular institution for girls, founding la Ligue socialiste des femmes (Socialist League for Women) then la Ligue de l’affranchissement des femmes (League for the Liberation of Women) and setting up a workers’ union for seamstresses.

Mme Astié de Valsayre, cartoon in Le Charivari, reproduced in John Grand-Carteret, La Femme en culotte (1899), Zut (Delaplanche’s pseudonym), September 1889, printed paper, © private collection

She called for the right to vote, women’s access to all studies and professions as well as equal pay. It was at this intense moment in her activity that she distinguished herself in the fight for a more rational female dress code. She herself wore masculine attire and demanded freedom of dress for women, lobbying the Police Prefecture (who did not bother to reply) and deputies through petitions. Her plea cited many of the unfortunate victims of tramway accidents, fires and drownings, “predestined to death” because of the clothes demanded of their gender. Deputies would reply that “no law requires women to wear complicated clothing”.

Adapting clothes to different physical and sporting activities was one of Astié’s concerns, one shared with other radical activists. She took up cycling, fencing and achieved scandalous fame fighting in a duel. A very common practice at the end of the 19th century, duelling was at the heart of the code of honour… an exclusively male one. Women, who had no access to this, are in a certain way assimilated to dishonoured and ineligible men.

The controversy over the right to duel occurred at the same time as the one described here, and featured the same protagonists: Astié, in particular, who had fought a duel at Waterloo with an Englishwoman over a dispute about the respective superiority of French and American female doctors. When, in 1890, the journalist Séverine was represented by her lover in a duel, Astié “severely reprimanded” her for not facing up to the responsibility of her actions. Twenty years later, Madeleine Pelletier, an admirer of Astié, would link the question of the masculinisation of women’s dress with that of women's right to fight off harassment by carrying a revolver, but also to defend themselves by duelling. To these campaigners for absolute equality between the sexes, the costume reform was inseparable from other feminist demands such as access to all professions, but also to education. It was a question of combating the repulsive image of the “bas-bleu” (blue stocking), considered, Astié explained, as a “hermaphrodite”, by reversing the aesthetic prejudices that idolised “feminine grace” and deemed “ugly” the “woman with a masculine physique”. The issue of the costume reform emerged at a time when feminism was asserting itself as a political force, successfully capturing the attention of the press and political parties.

« On dress », by Madeleine Pelletier

Madeleine Pelletier in her journal, La Suffragiste, put forward some autobiographical reflections on the “sartorial display” of her convictions which isolated her from other feminists.

“On dress”, by Madeleine Pelletier, La Suffragiste, n° 46, July 1919, p. 9.

“I am delighted to see our sister, La Lutte Féministe, campaigning for the virilisation of women’s dress codes.

“How happy you are to be freed of your clothes”, Hubertine Auclert used to tell me. Happy? How so? If you find it to be an advantage, do the same”.

She did not. Why not? I do not know. People who are bold in one area often think that they have to make amends for their audacity by remaining shy in all other areas.

Moreover, I have to say that all my life I have had to pay dearly for showing my feminist convictions through my dress, and I would add that it was in the so-called “progressive” circles that I was criticised the most. While my medical clientele accepted my short hair and my tailored suits, the socialists and even feminists couldn’t deal with it.

“You have to change your clothing habits”, Hervé used to tell me, “otherwise, you won’t have any influence. Just look at Louise Michel, she used to dress like every woman.” This was a weakness on her part that I will not imitate, as you say, to not lose all influence. I don’t stoop to human stupidity, too bad for her if she refuses to understand me, I won’t dress like a slave...

The provocative costume that women wear is the symbol of the permanent offer to the other sex that they make of themselves. Like the deformation of Chinese women’s feet, it is a mark of humiliating slavery.

If I dress the way I do, it is because it is comfortable, but especially because I am a feminist; my dress says to man “I am your equal”.

Men understood this well and this is why they wouldn’t admit it; […] I had a men’s suit made for me and I wore it. I was assured that I didn’t look too bad in it. MP.”

“On grooming” by Madeleine Pelletier

“On grooming” by Madeleine Pelletier, La Suffragiste, n° 46, January 1913.

1st part: Madeleine Pelletier analyses the differences between the sexes with regards to dress.

“Man dresses for life, women dress for love. In front of the mirror of his washroom, while arranging his hair and moustache, man is never not thinking about the effect he will have on woman. Yet if love is taken into consideration in the preparation of his face and tie, the rest of his adjustments are made above all for life.

He is first and foremost an individual. He is his own purpose. He must therefore be above all victorious in the battle for existence, so his clothes are aimed at practicality. The material is adapted to his body, his limbs, free, can perform all their movements without hindrance.

He is not indifferent to elegance, but he prefers to leave this to his suit. As long as his clothes are in unison with his social class, he is satisfied. Of course, there are some men who are more concerned about their exterior, who look for eccentric cuts, ties to this end, who spend a long time to grooming themselves. But the rest of their sex condemns them, and to show them this contempt, they call them effeminate: men who are like women.

As woman’s place in the struggle for life is growing, by force of circumstance, she is ceasing to dress solely for love. Farthingales, crinolines, and large and awkward dresses are disappearing to make way for the proper tailored suit with a tight skirt. Hats laden with furbelows are being replaced by supple felt with a simple ornament. It is more practical for street wear, easier to take off and hang on a peg. Gone, too, are the complicated undergarments, the many heavy starched petticoats our grandmothers used to lose their legs under. Jersey knickers, which are now in widespread use, mean that petticoats can be dispensed with, and many women today either do without them or wear only one” [...].

2nd part: Doctor Pelletier criticises the positions of feminists. Her rejection of the female gender earned her strong disapproval from the latter, for whom equality of the sexes did not necessarily mean the disappearance of “femininity”. Her relationship with radicals were hardly any easier… they were never radical enough in her eyes.

“[…] I’m sure I'll surprise more than one reader when I tell them that far from pushing for this development, feminist activists are actually fighting against it..

I confess that when I became an active feminist, I was saddened to see all those painted faces, heads adorned with flowers and birds, sometimes fresh, sometimes faded, depending on the purpose of their owners. I felt myself overwhelmed by the shame of belonging to such a frivolous sex. What a shame to dedicate the reason for one’s life to someone else, to spend hours doing one’s face, days matching the colour of a fabric with that of a ribbon, often with the most unsightly results. The woman who does this is not a person- she’s a doll, a puppet. She is not hers, she belongs to whoever wants her, for as long as he wants her. She is called a luxury woman, analogous to luxury dogs.

And what to say about the old ladies with plastered faces, painted lips whose servile smile seems to implore to the proud sex: am I not still desirable like this?

Of course, there can be no question of banishing love: without love there can be no humanity. But love must be based on equality and not on women offering themselves to men. A beautiful head will lose none of its charm if it is not adorned with birds.

Feminism does not outlaw elegance any more than love does. Our opponents claim that it does; but what do they not claim? A well-made suit is much more elegant than a chiffon dress, even by a good dressmaker. The woman who wears it gives the appearance of a person, of a thinking and willing being, a dress with frills only makes you think of a housewife when it is a cheap dress, of a courtesan when it is an expensive dress.

Feminists, as we have said, are showing themselves to be backwards in their ways. Far from being ahead of the mass of women, they are lagging behind. This can be explained by the slave-sex being naturally the timid sex, and the act of claiming rights seems so daring to the claimants themselves that they want to redeem their audacity by showing themselves to be more feminine in everything else than women who make no claims.

The feminist groups who worked on the costume reform achieved a result far inferior to that of fashion, which is nevertheless forced to take some inspiration from the necessities of life. They banned the corset altogether and adopted the robe dress. A few years ago, at a congress in Germany, I saw women dressed in the reformed costume. The flabby-fleshed obese women with their protruding bellies and sagging breasts looked as if they were nursing dozens of infants. It's a good thing to criticise the doll, but you mustn’t replace it with a female animal. You can’t breastfeed at a congress!

I can't stress this enough, ladies- women will only emancipate themselves by becoming more masculine. And don’t go off on a tangent saying that dress doesn’t matter. On the contrary, it matters a great deal. There’s a reason why soldiers wear uniforms and clerics wear habits. These men are dressed in a similar way, at least in the order of ideas to which the uniform corresponds. An independent mind, a powerful will, cannot live in lace garments, only a defective mind can take shelter under a grandmother’s bonnet. So have the courage, ladies, to be what you aspire to be.

A truly radical feminism

Feminism has always been associated with a willingness to masculinise women. A neologism of the 19th century, feminism originally referred to a pathology which would feminise men in modifying their secondary sexual characteristics. It was Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895), playwright and novelist, author of the very famous La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady of Camelias or Camille) (1848), who had the idea of distorting the word in 1872 in a little book, L'Homme-femme (“The Manwoman”), in which he strives to justify a husband’s murder of his adulterous wife. Feminists fought back – Maria Deraisme published Eve against Monsieur Dumas-fils in 1872… And they succeeded in rallying the writer to their cause who became involved in the divorce reform, the authorisation of paternity proceedings and women’s right to vote. These troubling origins left their mark, even after the word became commonplace at the end of the 19th century.

We have also seen how a minority of feminists demanded a certain degree of masculinity. Opponents to feminism tended to amalgamate everyone, despite these few not being representative of all activists.

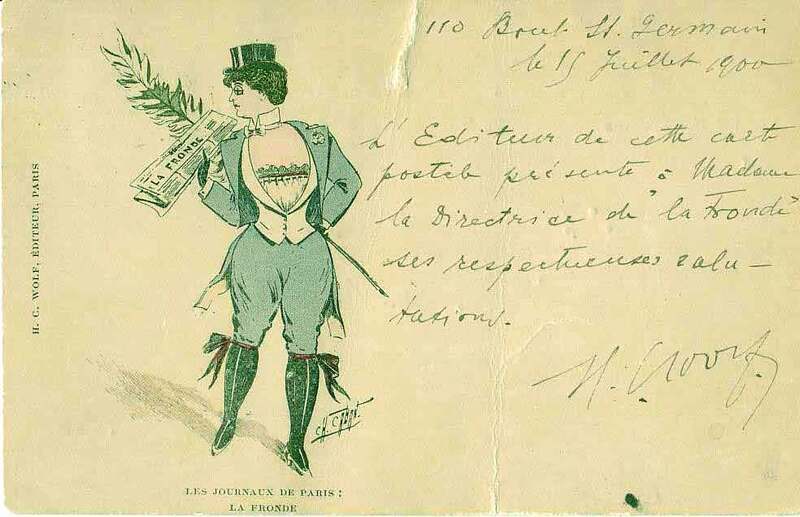

The most eloquent way of portraying a truly radical form of feminism was to suggest gender inversion, as did the author of this postcard in the famous daily newspaper founded in 1897.

Instead of representing Marguerite Durand, the founder of this newspaper, former actress and femme fatale in all her femininity, the illustrator decided to show a woman dressed as a man. La Fronde was written, put together, printed, and sold by women, giving it a very radical connotation. The illustration may possibly evoke Marc de Montifaud, a contributor to the newspaper and an authentic cross-dresser.

Masculinising a feminist to demean her is a commonplace practice. An example among many others would be the press during the trial of Hélène Brion, a feminist and pacifist schoolteacher. In March 1918, after four months in prison in St. Lazare, she appeared in front of the War Council. She defended herself brilliantly. Commentators searched for flaws in her personality, in her defence strategy, her behaviour and found the confirmation of their suspicions in an overly large pussy-bow. And the zouave culottes she wore to serve at the soup kitchen in Pantin fuelled many fantasies!

The masculine nature of feminist dress was first and foremost an invention destined to stigmatise. Nevertheless, the cliché intersects with reality in the rare cases where activists advocate this transgression.