Acting like a garçonne

With the garçonne (flapper) of the 1920s, the masculinising women finally gained legitimacy. It was fashionable, looked “young”, gave an “artistic”, ambiguous edge, and expressed “modernity”. Hair and skirts were shortened. It was a fairly brutal revolution, even if Paul Poiret’s pre-1914 models and wartime fashions had predicted this.

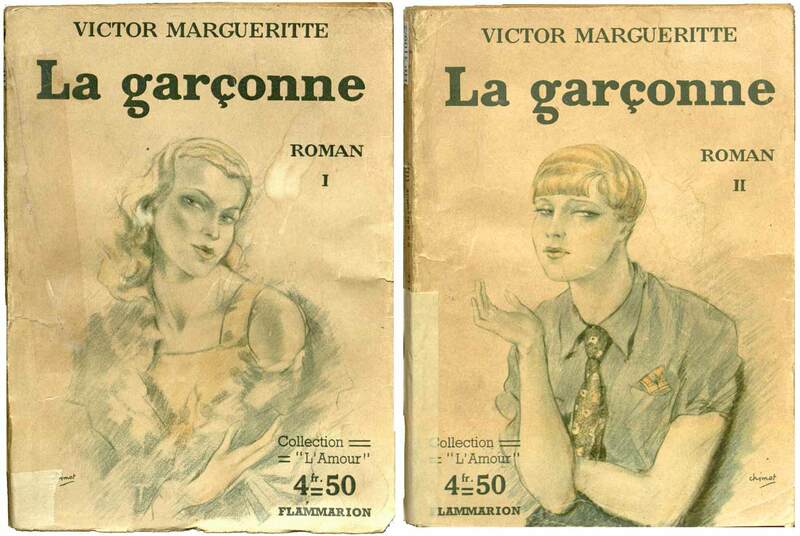

In 1922, Victor Margueritte’s novel was a huge success and a resounding scandal, giving a name to this fashion and moral phenomenon.

Chimot, a successful illustrator with a predilection for nude women, adorned these two covers of a cheap edition of La Garçonne. They show the metamorphosis of the eponymous heroine, a realistic Monique Lerbier. However, her style here belongs more to the 1930s than the 1920s (more typical of the Roaring Twenties would be the first illustrated edition (coloured with stencils) by Van Dongen). By way of “garçonning”, the feminine girl is transformed into an androgynous creature, in imitation of the fashion shown in advertisements and publications.

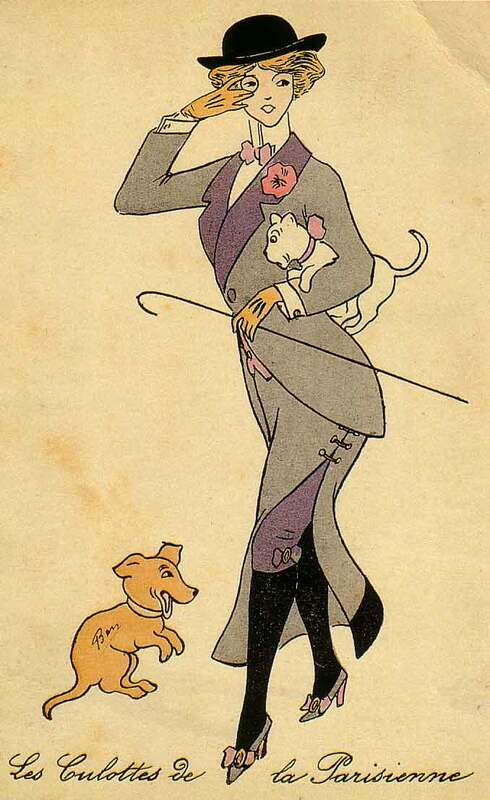

The premises of la garçonne. Paul Poiret’s Parisian woman

Paul Poiret (1879-1944), the most innovative designer of the Belle Epoque, set up on his own fashion house in 1904. Almost immediately, he declared “war” on the corset and launched a new silhouette, straight-lined, with the waist pulled up under the bust (Directoire style), in fine fabrics. Promoted by the beautiful illustrations of Paul Iribe and Georges Lepape, Poiret’s models were immediately adopted by Parisian fashion. His pronounced taste for the Orient inspired the puffed trousers covered with a short, flared skirt worn by his wife at the “Arabian Nights” evening organised by the couturier in 1913. During a trip to Vienna, he caused a scandal with his models donning culottes. The police had to intervene. The jupe-culotte was a failure on the eve of the war, but the couturier remained convinced that it would become fashionable sooner or later. He had no regrets about the corset which, he wrote, “imprisoned” women.

Paul Poiret is reputed to be the “liberator” of women, but the real creators of the 20th century silhouette were women: Chanel, Madeleine Vionnet. Paul Poiret was also the inventor of the “hobble skirt”, tapered and tight around the ankles, forcing women to walk with small steps. In his memoirs, the writer Maurice Sachs recounts the malicious pleasure he took in following a woman wearing this type of skirt, frightened and unable to run... Was Paul Poiret a feminist? Not really, judging by this extract from his memoirs, recalling his early days in his own boutique:

“It was still the time of the corset. I was waging a war against it. The last of these cursed devices was called the Gache Sarraute. Of course, I’ve always known women to be encumbered by their assets and anxious to conceal or distribute them. But this corset divided them into two distinct masses: on one side, the bust, the chest, and the breasts, on the other, the entire hindquarters, so that the women, divided into two lobes, looked like they were pulling a trailer. It was almost like going back to the way things were. Like all the great revolutions, this one had been made in the name of freedom, to give free rein to the stomach, which could expand without measure. It occupied the underside of the upper lobe.

It was also in the name of freedom that I urged the demise of the corset and the adoption of the brassiere, which has since made a fortune. Yes, I liberated the bust, but I hindered the legs. We all remember the weeping, screaming and gnashing of teeth caused by this fashion ukase. Women were complaining that they could no longer walk or ride in cars. All their whining argued in favour of my innovation. Are we still listening to their protests? Didn't they make the same moans and groans when they returned to full size? Did their complaints and grumblings ever stop the fashion movement, or did they on the contrary help to publicise it?

Everyone is wearing the tight skirt.”

Androgynous fashion

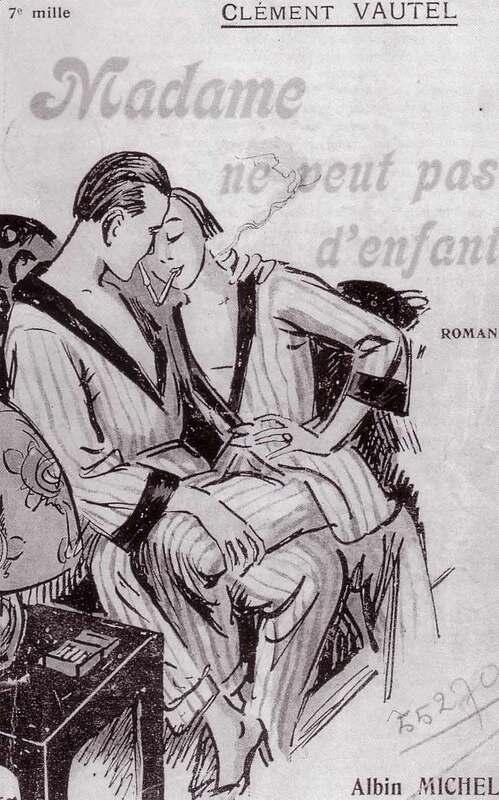

Women’s fashion had never looked so androgynous. Hair cut short “à la garçonne”, was quickly adopted by young women. They marked a change of era, an absolute revolution. Hips and buttocks were erased by the straight cut of low-waisted dresses. The corset was no longer there to constrict the waist and make breasts leap out. New women’s lingerie was light, fluid, silky, simplified and more respectful of the body. Advertisements showed small bras that sought to flatten breasts and girdles to hold stockings and slim down the body. The garçonne had to be thin. She had to be an adolescent in appearance. Youth and slimness became categorical imperatives. The models were as thin as today’s models. A whole market was created to obtain the desired weight. Cosmetic surgery was booming. If necessary, it corrected breasts, which in the 1920s were preferred discreet. Many authors, such as Clément Vautel, liken this fashion to the neo-Malthusianism practised, if not defended, by the French population between the wars.

“Madame doesn’t want any children”, says the journalist, well known for his anti-feminist views, because pregnancy would deform her body and threaten her independence... La garçonne or the “selfishness” of the “modern” woman.

If, despite everything, she gave in to the desire to have children, she would refuse to breastfeed, preferring the bottle, said journalists who saw this as the explanation for flapper fashion: breasts were no longer useful. Any physical reminder of motherhood was banned.

The infertile couple singled out by conservatives, wanted to be egalitarian. The illustrated cover of Clément Vautel’s novel speaks for itself. In this perfectly identical couple, the man and woman are barely distinguishable. Their fusion is evident in their pose, the symmetry of their positions, the contact between their heads and cigarettes, the similarity of their striped pyjamas. This fusion abolishes the sexes. It is androgynous.

| Working | Acting like a garçonne | Modernising |